- Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, Duke of Caxias

-

Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, the Duke of Caxias

The Duke of Caxias at age 75, 1878Nickname The Peacemaker

Iron DukeBorn August 25, 1803

São Paulo farm (present-day Duque de Caxias), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Portuguese Colony)Died May 7, 1880

Santa Mônica farm, Rio de Janeiro, BrazilAllegiance Empire of Brazil Rank Marshal of the army Battles/wars Independence of Brazil

Cisplatine War

Balaiada

Liberal rebellions of 1842

War of the Ragamuffins

Platine War

Paraguayan WarLuís Alves de Lima e Silva, Duke of Caxias (Portuguese pronunciation: [kaˈʃiɐs] or [kaˈʃiɐʃ]; 25 August 1803 – 7 May 1880), nicknamed "the Peacemaker"[1] and "Iron Duke",[2] was a monarchist, military officer and politician of the Empire of Brazil. Born into a family from the lower aristocracy, Caxias pursued a military career, as had his father and many relatives before him. In 1823, he fought as a young officer during most of the Brazilian War for Independence against Portugal. In 1825, he was deployed to Brazil's southernmost province, Cisplatina. He remained there for over three years while Brazil unsuccessfully attempted to prevent the province's seccession during the Cisplatine War. In the face of major protests during 1831, Caxias remained loyal to Emperor Dom Pedro I, even though his own father and uncles deserted the monarch. Nonetheless, Pedro I abdicated in favor of his young son, Dom Pedro II, whom Caxias eventually became friend and instructor in swordsmanship and horsemanship.

During the minority of Pedro II, the governing regency was faced with countless rebellions throughout the country. Once again, unlike his father and relatives who either joined or supported the rebellions, Caxias remained on the side of the lawful government. Given the command of loyal forces, from 1839 until 1845 he put down uprisings, including those known as the Balaiada, the Liberal rebellions of 1842 and the War of the Ragamuffins. In 1851, he led the Brazilian army in the victorious Platine War against the Argentine Confederation. A decade later, he held the rank of Marshal of the Army, the highest in the army. He was given the command over Brazilian forces in the Paraguayan War, in which he prevailed over the Paraguayans in a series of battles. As reward for his achievements, Caxias was raised to the titled nobility: first as baron, then count, marquis and lastly as duke. He was the only person to receive the honor of being made a duke during the 58-year-old reign of Pedro II.

In the early 1840s, Caxias became a member of the Reactionary Party—which eventually evolved into the Party of Order, and finally, into the Conservative Party. He was elected senator in 1846, and the Emperor appointed him president (prime minister) of the Council of Ministers for the first time in 1856. He briefly filled the office again in 1861, but fell when his cabinet lost its majority in the Parliament. Over the decades, Caxias witnessed the growth, apogee and slow decline of his party, which became divided and weakened by internal conflicts. In 1875, old and sick, he headed a cabinet for the last time. After years of failing health, he died on 7 May 1880.

For decades after his death and the downfall of the Brazilian monarchy, Caxias's exploits were largely ignored. His legacy was slowly rehabilitated over time. In 1925, his birthday was selected to become the official "Day of the Soldier", which honors the Brazilian Army to the nation of Brazil. On 13 March 1962, he was officially designated as the army's tutelary patron, and is held as both its paradigm and the most important figure in its tradition. Historians have regarded Caxias in an extremely positive light, and he is usually ranked as the greatest Brazilian military officer.

Contents

Early years

Birth and childhood

Luís Alves de Lima e Silva was born on 25 August 1803.[3][4] His birthplace was a farm called São Paulo (today within the city of Duque de Caxias) located in the captaincy of Rio de Janeiro.[3][5] He was the second eldest child (but first son) out of ten children[6] to Francisco de Lima e Silva and Mariana Cândido de Oliveira Belo.[7][8] Luís Alves' godparents were his paternal grandfather, José Joaquim de Lima da Silva,[A] and his maternal grandmother, Ana Quitéria Joaquina.[5]

Although he would eventually become one of the most important figures in Brazilian history, there is only scant information regarding Luís Alves' life prior to age 36, at which point he was chosen to suppress the Balaiada rebellion.[9] It is known that his early years were spent on the São Paulo farm owned by his maternal grandfather, and namesake, Luís Alves de Freitas.[5] The young boy may have been initially schooled at home, as was common then. He also may have learned to read and write from his grandmother, Ana Quitéria.[10]

The arrival of the Portuguese Royal Family in Rio de Janeiro in 1808 changed the lives of the Lima family.[11] King Dom João VI embarked upon a series of wars of conquest which resulted in the expansion of Brazil's territory with the annexation of Cisplatina to the south and of French Guiana to the north.[12] By 1818, Luís Alves' relatives who were military officers and had served in the wars had been ennobled. His grandfather, José Joaquim became a member of the Order of Christ and fidalgo cavaleiro da Casa Real (knight noble of the Royal House).[13] His father, Francisco de Lima, and uncles were also granted honors.[14] Within a span of two generations, the Lima family had risen from mere commoners into the ranks of Portugal's untitled nobility.[15]

Military education

On 22 May 1808, Luís Alves was enlisted at the age of 5 as a cadet in the 1st Regiment of Infantry of Rio de Janeiro.[16][10] Historian Adriana Barreto de Souza explained that this did "not mean that he began to serve as a child, the connection to the regiment was simply honorific", a perquisite open to Luís Alves as the son of a military officer.[3][10] This infantry regiment was informally known as the "Lima [family] Regiment" because so many members of the family served in it, including Luís Alves' father and grandfather.[17]

In 1811, Luís Alves moved with his parents from his grandparents' farm to Rio de Janeiro and was enrolled at the Seminário São Joaquim (Saint Joachim's School).[18][10] Seven years later, on 4 May 1818, he was admitted into the Royal Military Academy.[19] On 12 October 1818 he was promoted to the rank of alferes (equivalent to a second lieutenant today) and to lieutenant (nowadays first lieutenant) on 4 November 1820.[19] A young man of regular features, Luís Alves had an average height,[20][2] a round face,[21] brown hair and brown eyes.[20][2] He was considered a very reasonable[22] and honest person.[23] Historian Thomas Whigham described him as someone who "learned the art of giving orders early in life. Immaculate in his dress, he was soft spoken, polite, and smoothly in control of himself. He seemed to radiate calm composure and authority."[24]

In the Royal Military Academy he followed the course of Infantry.[25] To graduate as an infantryman, he was supposed to take classes of the 1st and 5th year, which he did in 1818 and 1819, respectively.[26] Although the entire course (which ran from the 1st to 7th year) was only mandatory to artillerymen and engineers, Luís Alves opted to take classes of the 2nd year in 1820 and of the 3rd year in 1821.[27] He took classes that ranged from arithmetic, algebra and geometry to tactics, strategy, camping, fortification in campaign and terrain reconnaissance.[25] Albeit an accomplished student, the young Lieutenant was often reprimanded for bullying newbies.[28]

Between family and loyalty to the crown

Independence of Brazil

Main article: Independence of BrazilLuís Alves would normally have begun his 4th year classes at the Royal Military Academy sometime in March 1822.[29] Luís Alves dropped out of the academy in December 1821 and enlisted in the 1st Fusilier Battalion.[19][30] Prince Dom Pedro, son and heir of King João VI, had just embarked upon the struggle against Portugal that led to the independence of Brazil on 7 September 1822.[31] The Prince was later acclaimed Dom Pedro I, first Brazilian emperor, on 12 October.[32] Those Brazilian and Portuguese forces who remained loyal to Portugal refused to accept this outcome, which led to a war fought on several fronts across Brazil's provinces.[33]

On 18 January 1823, Pedro I created the "Emperor's Battalion", an elite infantry unit composed of men handpicked by himself.[34][35] One of those selected for the new battalion was Luís Alves. He was named as adjutant to the company's commander, who happened to be his uncle, Colonel José Joaquim de Lima e Silva.[36] The Emperor's Battalion was sent to the province of Bahia (in the Brazilian northeast) on 28 January.[37] Upon arrival, it was placed, along with other troops, under the command of French Brigadier General Pierre Labatut. The Brazilian Imperial forces besieged Bahia's capital, Salvador, which was held by the Portuguese.[37] During the siege, Luís Alves fought in at least three attacks (on 28 March, 3 May and 3 June) against Portuguese positions around Salvador, all successful. In the engagement on 28 March, he personally led a charge on an enemy bunker.[38][39][40]

During the Bahia campaign, high ranking officers mutinied against Labatut, who was taken prisoner and sent back to Rio de Janeiro.[41] It is unlikely that Luís Alves was involved,[B] but his uncle Joaquim de Lima was almost certainly part of the conspiracy and was chosen by the officers to replace Labatut. The campaign resumed, and the Portuguese withdrew from Salvador and set sail back to Portugal. On 2 July. the victorious Brazilians entered the city.[42][43] The Emperor's Battalion returned to Rio de Janeiro, and Luís Alves was later promoted to captain on 22 January 1824.[19][44][39]

Cisplatine War and father's betrayal

See also: Cisplatine WarThe Portuguese garrison in Montevideo, which was the capital of Cisplatina (then Brazil's southernmost province), was the last to surrender.[45] In 1825, secessionists in the province rebelled. The United Provinces of South America (later Argentina) attempted to annex Cisplatina. Brazil declared war on the United Provinces, triggering the Cisplatine War.[46] The Emperor's Battalion, to which Luís Alves was still attached, was sent to guard Montevideo, then besieged by rebel forces. Luís Alves fought in engagements against the insurgents during 1827 (7 February, 5 July, 7 July, 14 July, 5 August and 7 August).[47][48]

The war came to a disastrous end in 1828 with Brazil's relinquishment of Cisplatina, which became the independent nation of Uruguay.[49] Nonetheless, Luís Alves was promoted to the rank of major on 2 December 1828 and placed as second-in-command of the Emperor's Battalion in early 1829.[19][48] During his stay in Montevideo, he met María Ángela Furriol González Luna.[50][51] How far their relationship progressed is unknown but they may have been in a failed engagement. Luís Alves returned to Rio de Janeiro and witnessed the increasing decline in Emperor Pedro I's political position. A growing opposition to Pedro I's policies eventually erupted into mass protests in the Field of Santana, in downtown Rio de Janeiro, on 6 April 1831. The situation grew more ominous when several military units, led by Luís Alves's father and uncles,[52][53] joined the protests.[54]

The Emperor considered appointing Luís Alves to command the Emperor's Battalion and asked him which side he would choose.[55] According to historian Francisco Doratioto, Luís Alves answered that "between the love of his father and his duty to the crown, he would stay with the latter."[56] Pedro I expressed gratitude for his loyalty, but instead ordered him to lead the Emperor's Battalion to go to the Field of Santana and join the rebels.[57] The Emperor preferred abdication to civil war.[58] Many decades later, Luís Alves would say in the Brazilian Senate: "I marched along with the Emperor's Batallion to the Field of Santana, out of devotion to competent orders [from Pedro I]. I was not a revolutionary. I esteemed the Abdication. I judged that it would be of advantage to Brazil, but I did not concur directly or indirectly with it."[59][58]

Marriage

A regency of three was elected to rule until the five-year-old Dom Pedro II (Pedro I's son) reached the age of majority and the ability to rule in his own right. One of the regents chosen was Luís Alves' father, Francisco de Lima e Silva.[60] The army, "demoralized by the far from exemplary part it had played in the April Revolution [i.e. Pedro I's abdication]," said historian C. H. Haring, "became the ready tool of any popular agitator or demagogue, and often the source of riot and sedition."[61] With no other option, the government severely reduced the size of the standing army contigent, and effectively replaced it with the newly created National Guard, a militia force.[62] In October 1831, and without troops to command, officers (including Luís Alves) joined the Volunteer Soldier-Officers Battalion, acting as soldiers.[63] A year later Luís Alves was appointed commander of the Permanent Municipal Guard Corps, a police force in the city of Rio de Janeiro.[64]

On 6 January 1833, at age 29, Luís Alves married Ana Luísa de Loreto Carneiro Viana, aged 16 and younger sister of an army officer friend. She was also a member of an aristocratic family of Rio de Janeiro. The marriage took place contrary to the wishes of the bride's mother, who saw Luís Alves and his family as upstarts. Newspapers connected to political enemies of his family took advantage of this disagreement to level serious, but unfounded, accusations against him, including that he had kidnapped Ana Luísa.[65] Despite the invective, their marriage was a happy one[66][67] and three children resulted: Luísa de Loreto Viana de Lima, Ana de Loreto Viana de Lima and Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, born in 1833, 1836 and 1847, respectively.[68]

In the late 1830s Luís Alves was appointed instructor in swordsmanship and horsemanship to the young Pedro II.[69] Ties of duty had drawn the two men together, but a long-lasting friendship and personal devotion also developed. Pedro II said many years later that he regarded Luís Alves as "loyal and my friend".[70] According to historian Heitor Lyra, Luís Alves was "one of the rare, sincere and profoundly convicted monarchists and friends of the King [i.e., the Emperor] and of the Dynasty [the House of Braganza] He placed his sword not only in service to a united and strong Brazil, but also to a worthy and respected Monarch".[71]

Quelling rebellions

Balaiada

Main article: BalaiadaAs the commander of the Permanent Municipal Guard Corps, Luís Alves managed to bring peace and order to the streets of Rio de Janeiro. This accomplishment resulted from both his own skill and his partnership with Rio chief of police, Eusébio de Queirós.[72] Luís Alves was raised from major to lieutenant colonel on 12 September 1837.[73] Eusébio was a member of the Partido Regressista (Reactionary Party), which had come to power in that year. Bernardo Pereira de Vasconcelos, one of the leading Reactionaries and a government minister, attempted to attract Luís Alves to his party.[74]

After being promoted to colonel on 2 December 1839,[73] Luís Alves was sent by the Reactionary cabinet to the province of Maranhão to quell a rebellion which became known as Balaiada. He was appointed to the highest civilian and military positions in the province: presidente (president or governor) and comandante das armas (military commander), thus giving him authority over the National Guard and army (brought back to its full strength by the Reactionary administration)[75] units in the province, respectively.[76]

Luís Alves arrived in São Luís (Maranhão's capital) on 4 February 1840.[77] After several battles and skirmishes, the rebels were defeated.[78] For his achievement, Luís Alves was promoted on 18 July 1841 to brigadier (present-day brigadier general) and raised by Pedro II to the titled nobility as Barão de Caxias (Baron of Caxias). He was allowed to chose his title, a rare honor, which he did to commemorate his recapture of Caxias, Maranhão's second richest town which had previously fallen into rebel hands.[79][80] Francisco de Lima wrote to his son with news of Liberal's demand that Pedro II's majority be immediately declared.[68] Meanwhile, Honório Hermeto Carneiro Leão (later Marquis of Paraná, a distant cousin of Caxias' wife[81] and a head of the Reactionary Party) sent letters to Luís Alves attempting to undermine the influence Francisco de Lima held over him and to dissuade him from supporting the unconstitutional proposal to declare the Emperor of age.[82]

Liberal rebellions of 1842

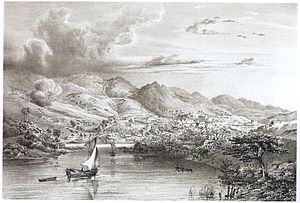

Sabará (pictured) was one of the towns Caxias marched into during the 1842 Liberal rebellion in Minas Gerais province

Sabará (pictured) was one of the towns Caxias marched into during the 1842 Liberal rebellion in Minas Gerais province

Upon his return from Maranhão, Caxias saw that the political climate had changed. Francisco de Lima's Liberal Party had successfully pushed through the Emperor's premature declaration of majority on 23 July 1840.[83] On May 1842 the Liberals rebelled in the provinces of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Minas Gerais. It was a retaliation against the Emperor's decision—under the advice of a Council of State dominated by Reactionaries—to call for new elections, annulling the previous election in which the Liberal Party had tainted the results by widespread fraud.[84][85]

Named as the province's vice-president and military commander, Caxias arrived in São Paulo on 21 May 1842. Once he defeated the rebels there, he was appointed as military commander of Minas Gerais and marched to this province. With the aid of National Guard units from Rio de Janeiro under its president, Honório Carneiro Leão, Caxias was once again successful, and by late August, the rebellion was crushed.[86] Caxias was honored by Pedro II, who made him his Aide-de-Camp on 23 July 1842. Two days later Caxias was promoted to temporary (brevet) field marshal (present-day divisional general).[87]

To distinguish itself from what the Reactionaries perceived as the "unruly" Liberals, sometime around 1843 (and certainly by 1844), the Reactionary Party became known as the Partido da Ordem (Party of Order) and its members as saquaremas.[88] Caxias increasingly identified himself with the saquarema ideology:[C] liberalism, preservation of the authority of the state, and support for representative parliamentary monarchy.[89] Although his move toward the saquarema camp was not clear at the time he accepted the appointment to put down the rebellion in Maranhão in 1839, his victory over the Liberal rebels in 1842 only further solidified his fidelity to the Party of Order.[90]

War of the Ragamuffins

Main article: War of the RagamuffinsWhen the republican secessionist rebellion known as War of the Ragamuffins began in Rio Grande do Sul in 1835, an uncle of Caxias (died 1837) joined the rebels.[91] His father, Francisco de Lima,[92] and possibly another uncle (who was Minister of War at the time),[93] secretly supported the rebellion. On 28 September 1842, Caxias was appointed president and military commander of the province of Rio Grande do Sul.[94] The 16-year-old Pedro II allowed Caxias to prove once more that he was unlike his father and uncles and gave him a short and direct order: "End this revolution, as you have ended the others."[94] Caxias brought with him a fellow saquarema and famous poet Domingos Gonçalves de Magalhães (later Viscount of Araguaia) to serve again as his secretary, as he had previously in Maranhão.[95]

Caxias had previously made a short trip to Rio Grande do Sul in 1839 to inspect the war effort against the Ragamuffins.[96] Upon his return to the province in November 1842, he found that the rebels had been severely weakened after years of struggle and had been forced to resort to guerrilla warfare. When threatened, the rebels escaped to safety in nearby Uruguay (former Cisplatina). As he did in Maranhão,[97] São Paulo[98] and Minas Gerais,[99] Caxias planted spies within enemy ranks to gather information and to foment dissention.[100] Historian Roderick J. Barman said that he "displayed military, organizational, and political talents essential to what is now termed 'counterinsurgency.'"[101]

In early 1843, Honório became the head of the cabinet, and so long as the saquaremas remained in power, Caxias was safe in his position. A year later, Honório and the saquaremas resigned after he quarreled with Pedro II.[102][103][104] The Liberals replaced the saquaremas in government, but Caxias was retained in his command.[105] The War of the Ragamuffins took far longer to put down than had previous rebellions, but through careful negotiation and military victories, Caxias finally managed to pacify the province. The end of the armed conflict was declared on 1 March 1845.[106] He was made permanent field marshal on 25 March and raised to count on 2 April.[107] Caxias ran for a Senate seat, and being among the three candidates with the most votes, he was selected by the Emperor in late 1845 as the senator representing Rio Grande do Sul.[108] He took his Senate seat on 11 May 1846.[109]

Conservatism

Platine War

Main article: Platine War Caxias traveled aboard the steamship Dom Afonso (pictured) and took stock of the port area of Buenos Aires, the Argentine capital, selecting the best place to launch a later aborted amphibious attack during the Platine War

Caxias traveled aboard the steamship Dom Afonso (pictured) and took stock of the port area of Buenos Aires, the Argentine capital, selecting the best place to launch a later aborted amphibious attack during the Platine War

After years as opposition in the parliament, in September 1848 the Party of Order was called upon by Pedro II to form a new cabinet.[110][111][112] The saquarema cabinet was composed of men with whom Caxias had close relationships, among them Eusébio, who had helped him bring order to the streets of Rio de Janeiro in the late 1830s.[113] Caxias was now a wealthy planter who owned several slaves and was very much a part of the landed aristocracy that formed the backbone of Party of Order. He purchased, with the help of his wealthy mother-in-law, his first piece of land, from which he created a coffee farm in 1838.[114] He acquired more lands in 1849.[115] Due to growing international demand, coffee had become the most valuable export commodity in Brazil's foreign trade.[116][117]

In 1851 when Don Juan Manuel de Rosas, dictator of the Argentine Confederation, declared war on Brazil. Caxias was appointed commander-in-chief of the Brazilian land forces tasked with fighting the Argentines. The Minister of Foreign Affairs, Paulino Soares de Sousa (later Viscount of Uruguai), forged an anti-Rosas alliance between Brazil, Uruguay and rebel Argentine provinces. When Paulino asked who should be appointed to be Brazil's representative among the allied forces participating in the theater of war, Caxias suggested Honório's name.[118][119] Honório, who had been ostracized by his peers after his fall in 1844, was the saquarema closest to Caxias.[120]

The army commanded by Caxias crossed into Uruguay in September 1851.[121][122] The allies decided to divide their forces into two armies: a multinational force that included a single Brazilian division, and a second army composed entirely of Brazilians under Caxias. To lead the Brazilian division attached to the multinational force, Caxias opted (against the wishes of Honório) for Manuel Marques de Sousa (later Count of Porto Alegre).[118][119]

Caxias met and befriended Manuel Marques, who served under his command in the War of the Ragamuffins, during his trip to Rio Grande do Sul in 1839.[119] The Brazilian division led by Manuel Marques, along with Uruguayan and Argentine rebel troops, invaded Argentina. On 3 February 1852, in the Battle of Caseros, the allies defeated an army led by Rosas, who fled to the United Kingdom thus ending the war.[123][122] Caxias spent 17 February aboard the frigate Dom Afonso (commanded by John Pascoe Grenfell) taking stock of the port area of Buenos Aires, the Argentine capital, selecting the best place to launch an amphibious attack. His plan was aborted once the news of the victory in Caseros arrived.[124] As a reward for his role in bringing about the victory, Caxias was promoted to lieutenant general on 3 March and raised to marquis on 26 June.[125]

Conciliation cabinet

See also: September 6, 1853 cabinetAround 1853 (and certainly by 1855), the old Party of Order had become more widely known as the Conservative Party.[126] The year 1853 was a milestone in Caxias's life, as his father Francisco de Lima died in December. For years, father and son clashed from opposite sides. The Marquis ultimately prevailed, adhering closely to his grandfather José Joaquim de Lima's steadfast loyalty to the Crown and respect for the law. By the time of his death, Francisco de Lima, a senator in his own right, had long lost his former influence and had not held any office of importance for years. Nevertheless, Caxias and Francisco de Lima maintained a loving and respectful relationship to the very end, as may be seen in the few surviving letters exchanged between them.[114] His interaction with other family members, however, was marred by resentments, as he told his wife years later: "We are placed in the foreground of our society, causing even envy to your relatives and to my mine as well."[127]

On 14 June 1855, the Marquis accepted the portfolio of minister of war and joined the "Conciliation cabinet" headed by Honório (now Marquis of Paraná). Caxias and Paraná had also known each other since 1831 and had formed a deep friendship and strong bond based on trust[128] and views shared in common.[129] Paraná had been meeting with an overwhelming opposition in parliament from members of his, and Caxias's, own party.[130] Under the guise of correcting flaws in elections so that all parties would have legitimate access to representation in parliament, Paraná attempted to pass electoral reforms that would, in practice, allot cabinets even more influence to meddle in elections through coercion and patronage.[131] The saquaremas understood the threat: it would undermine their own party (in fact, any party) by strengthening the executive branch to the detriment of the legislative.[132]

In search of broader support, Paraná appointed as ministers politicians who had few, or no, links to the saquaremas. Caxias was a saquarema, but according to Needell, he "was first and foremost a military man. Personal fealty to the Empire came before any other. As so many did, he identified this loyalty with fealty to the Crown in abstraction and to Dom Pedro personally."[129] He was a choice that could please all sides. Caxias, said Needell, "was not so much a political man as a man profoundly loyal to the Monarchy with which he ... had come to identify with the Conservative Party. Thus, Paraná may have appointed Caxias to reassure traditional Conservatives without endangering the more independent political position Paraná was taking."[129]

Failed presidencies of the Council of Ministers

Paraná eventually succeeded in passing electoral reform, which was called Lei dos Círculos (Law of the Circles).[133] As predicted, and feared, it gave greater powers to president of the Council of Ministers to meddle in elections. Unexpectedly, Paraná fell ill and died on 3 September 1856.[134] Caxias replaced him, but he was reluctant to face the legislature, elected under the electoral reform, that was slated to convene the next year. He resigned, along with the other cabinet ministers, on 4 May 1857. The Law of the Circles and the controversy surrounding it split the Conservative Party down the middle: the first faction was the saquarema ultraconservative (or tradionalist) wing, then called vermelhos (reds) or puritanos (puritans), and was led by Eusébio, Uruguai and Joaquim Rodrigues Torres, Viscount of Itaboraí. The second bloc comprised the conservador moderado (moderate Conservative) wing, which supported the conciliation agenda and was composed mostly of younger politicians who owed their positions to electoral reform.[135]

The moderate Conservatives lacked fidelity to saquarema ideology and leadership. They were Conservatives in name only. During the years following 1857, successive cabinets quickly collapsed, unable to muster majority votes in the Chamber of Deputies, as the two Conservative wings undercut each other in a fight for dominance.[136] The Emperor asked Caxias to head a new cabinet on 2 March 1861.[137] Among his ministers, were José Maria da Silva Paranhos (later Viscount of Rio Branco), whom Caxias met and befriended during the Platine War while serving as secretary to Paraná.[129]

Caxias tried to secure support from the traditional saquarema leadership. They attempted, instead, to use him as a figurehead and to further their own agendas. He commented to Paranhos: "I see what you meant, with respect to the bizarre behavior of these gentlemen, who do not wish to govern the country, when they are invited to do so, because they prefer to govern the Government. They are completely mistaken about me, since I am not disposed to serve them as a hobbyhorse."[138]

Lacking support in parliament, Caxias' cabinet resigned on 24 May 1862 after losing its majority in the Chamber of Deputies (the national legislature's lower house). Pedro II asked members of the Liga Progressista (Progressive League)—a new party consisting of moderate Conservatives and Liberals—to form a new cabinet.[139][140] Barely a month later, Caxias's only son died at age 14 of unknown causes.[141] There was a small consolation at the end of 1862 when, on 2 December, he was made temporary marechal do exército (marshal of the army), the highest rank in the Brazilian army.[141]

Paraguayan War

Main article: Paraguayan WarSiege of Uruguaiana

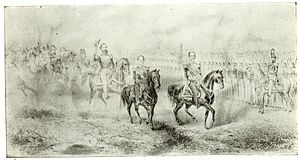

Pedro II (raising his hat) follows behind his two aides-de-camp, one of them is Caxias (center). This military parade most probably occurred in the Siege of Uruguaiana at the beginning of the Paraguayan War

Pedro II (raising his hat) follows behind his two aides-de-camp, one of them is Caxias (center). This military parade most probably occurred in the Siege of Uruguaiana at the beginning of the Paraguayan War

In December 1864, the dictator of Paraguay, Francisco Solano López took advantage of Brazil's military intervention in Uruguay to establish his country as a regional power. The Paraguayan army invaded the Brazilian province of Mato Grosso (currently the state of Mato Grosso do Sul), triggering the Paraguayan War. Four months later, Paraguayan troops invaded Argentine territory in preparation for an attack upon the Brazilian province of Rio Grande do Sul.[142]

The situation in Rio Grande do Sul was chaotic and the local military commanders were incapable of mounting an effective resistance against the Paraguayan army. Pedro II, aware of the danger, decided to go to the front in person to shore up operations.[143] As the Emperor's military aide-de-camp, Caxias followed his monarch into the combat zone.[144][145] The Marquis had warned the Progressive cabinet that Brazil was unprepared to intervene in Uruguay and even less prepared to resist a foreign invasion. His warnings were ignored and he complained, with a bit of irony, to his friend João Maurício Vanderlei, Baron of Cotejipe, a former colleague in the Conciliation cabinet: "I am almost mad with the mistakes that I am seeing being made, but since I am a red [ultraconservative or traditional saquarema] I am not listened since everything is progress in our country."[146]

The Imperial party arrived in Rio Grande do Sul's capital, Porto Alegre, in July 1865. From there, they traveled inland until they reached Uruguaiana in September.[147][148] This Brazilian town had been occupied by a Paraguayan army. By the time Caxias and his party arrived, the town was under siege by a combined force made up of Brazilian, Argentine and Uruguayan units—the latter had allied with Brazil against Paraguay. The Paraguayans surrendered without further bloodshed, freeing the Emperor and Caxias to return to the Imperial capital.[149][150]

Commander-in-Chief

The Allies next invaded Paraguay in April 1866 and, after an initial success, their advance was blocked by fortifications at Humaitá, which blocked further progress both by land and along the Paraguay River . The Progressive cabinet decided to create a unified command over Brazilian land forces operating in Paraguay, and it turned to the 63-year old Caxias (made permanent marshal of the army on 13 January)[151] as the new head on 10 October 1866.[152][153][154][155][156] He explained to his wife that the reason he had accepted the post was because the war "was an evil that has reached more or less all, from the Emperor to the most unfortunate slave."[155]

Caxias arrived in Paraguay on 17 November,[157] and assumed, for all practical purposes, the supreme command of both land and naval forces in the war, even though he had not explicitly been given authority over the navy.[158] His first measure was to dismiss Vice-Admiral Joaquim Marques Lisboa (later the Marquis of Tamandaré and also member of the Progressive League) and appoint fellow Conservative, Vice-Admiral Joaquim José Inácio (later the Viscount of Inhaúma), to lead the navy.[159]

From October 1866 until July 1867, all offensive operations were suspended.[160] During this period, Caxias trained the soldiers, re-equipped the army with newer guns, improved the quality of the officer corps, and upgraded the health corps and overall hygiene of the troops, putting an end to epidemics.[161] Alfredo d'Escragnolle Taunay (later the Viscount of Taunay), who fought in the war, remembered that Caxias was a "generous military chief, who forgave small errors, but was implacable with those who commited grave misdeeds, or, then, who betrayed his confidence."[23]

With the Brazilian army ready for combat, Caxias began the operation to encircle Humaitá and force its capitulation by siege. To aid the operation, Caxias used observation balloons to gather information on enemy lines.[162] The combined Brazilian-Argentine-Uruguayan army advanced through hostile territory in the effort to surround Humaitá. By 2 November, Humaitá was completely cut off from overland reinforcement by Paraguayan forces.[163] On 19 February 1868, Brazilian ironclads successfully made a passage up the Paraguay river under heavy fire, assuming full control of the river and thus isolating Humaitá from resupply by water.[164]

Dezembrada

The relationship between the Marquis of Caxias—now the Allied Commander-in-Chief[D]—and the governing Progressives worsened until it became a political crisis that led to the cabinet resignation. The Emperor called Conservatives, under Itaboraí leadership, back into power on 16 July 1868.[165][166] The Allies occupied Humaitá on 25 July after López managed to engineer a successful withdrawal of all Paraguayan troops from its fortress.[167]

Pressing his advantage, the Marquis began organizing an assault on the new Paraguayan defenses which López had thrown up along the Pikysyry, south of Asunción (Paraguay's capital). This stream afforded a strong defensive position which was anchored to the northwest by the Paraguay River and on the southeast by the swampy jungle of the Chaco region, both of which were considered to be nearly impassible by a large force. Rather than making a frontal attack on López's line, Caxias had a road cut through the Chaco region. The road was finished, undetected by López by early December, allowing the Allied forces to outflank the Paraguayan lines and attack from the rear.[168] In three successive battles (Ytororó, Avay and Lomas Valentinas), which became known as Dezembrada (Deed of December), the combined Allied forces completely annihilated the Paraguayan army. López himself barely managed to escape with a few followers,[169][168][170] and on 1 January 1869, the Brazilians occupied Asunción.[171][172] According to historian Ronaldo Vainfas, "his perfomance ahead of the Allied forces contributed in an unquestionable way to the final triumph over the enemy."[173]

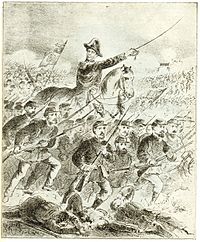

The Marquis had to take great risks to accomplish those victories. In the Ytororó engagement, which occurred on 5 December, the Allied objective was to take a bridge over Ytororó river. Several attempts were made cross the bridge, but each was repelled by intense fire from the Paraguayan positions. In a final attempt, the Brazilian soldiers panicked and began to flee in disorder. Caxias, witnesseing the impending disaster, unsheathed his sword and charged on horseback toward the bridge, followed by his staff. He passed through the fleeing troops shouting "Hail to His Majesty", "Hail to Brazil" and finally, "Sigam-me os que forem brasileiros!" ("Those who are true Brazilians follow me!"[174]).[175][176] The display stopped the retreat immediately, allowed the units to regroup and, in a vigorous attack led personally by Caxias, overwhelmed the Paraguayan positions.[175][177] Several men who were next to him during the attack were killed, as well as his own horse.[175]

Aftermath

Caxias, around age 66, wearing the collar of the Order of Pedro I, c.1869

Caxias, around age 66, wearing the collar of the Order of Pedro I, c.1869

Caxias was growing old, and was ill and exhausted by the time he reached Asunción. As he did not feel up to the task of pursuing López into the Paraguayan hinterland, he asked to be either relieved of his post or to take a short leave in order to recover. Although his request was denied, Caxias appointed a senior member of his staff as acting-commander and left for Brazil on 19 January 1869.[178] The Emperor was angered that the Marquis had left his post without permission, and especially that Caxias had declared the war to have been already won—even though López was still at large and regrouping his few remaining military assets. Caxias' ill conceived decision seriously endangered the hard-won achievements of the past months, even as the objective of eliminating López as a threat remained tantalizingly within reach.[178]

The Marquis arrived unannounced in Rio de Janeiro in early February.[179] He went directly to his home, to the surprise of his wife, who—like everyone else—was not aware that he had returned.[179] Pedro II was greatly disappointed in Caxias, though he was also very aware that the Marquis was the person most responsible for the great successes during the war and that these accomplishments had come at the cost of years of sacrifice and personal bravery. The Emperor called the Marquis to the Imperial Palace, the Paço de São Cristóvão, on 21 February 1869 and they reconciled.[180][181]

A few days later, Caxias was awarded the Order of Pedro I and was raised from marquis to duke, the highest rank in Brazilian nobility. These were distinctions that no other individual received during the long, 58-year reign of Pedro II.[179] The Emperor also later appointed him to the Council of State on October 1870. Nonetheless, this did not shelter Caxias from being subjected to attacks and accusations—some petty—in the parliament, including for having left his post without permission.[182] The embittered Duke wrote to his friend Manuel Luís Osório, Marquis of Erval: "When I was young, my friend, I did not know how to explain the reason why the elderly were selfish, but now that I am old, I see that they are like that because of the disappointments and ingratitudes they suffer during their lives. At least this is what happens to me".[183]

Later years

Figurehead presidency

Paranhos, now Viscount of Rio Branco, led a cabinet which lasted from 1871 to 1875. Two serious crises arose that challenged its viability and undermined the foundations of the monarchy itself. The first was resulted from the controversy over the Law of Free Birth, which Caxias supported and voted in favor of its approval. The law emancipated children born to slave women after its enactment. With half of its members supporting it and the other half staunchly opposed, a serious rift was opened within the Conservative Party. The opponents represented the interests of powerful coffee farmers like Caxias himself, who were long the main political, social, and economic support of the Conservative Party.[184]

The second crisis developed after the government entered into a conflict with two bishops who had ordered Freemasons expelled from lay brotherhoods. The dispute grew out of proportion when both bishops were convicted and given prison sentences for having disobeyed the government's order to rescind their expulsions of Freemasons.[185] As Catholicism was the state religion, the Emperor exercised, with the Papacy's acquiescence, a great deal of control over Church affairs—paying clerical salaries, appointing parish priests, nominating bishops, ratifying papal bulls, and overseeing seminaries.[186] As a result of the furor over the handling of the affair, Rio Branco and his cabinet resigned, "disunited and weary after four years in office", according to historian Roderick J. Barman.[187] Pedro II asked Caxias to form a new cabinet. The Duke later gave a remarkable account of their meeting:

Believe that when I entered my carriage to go São Cristóvão, summoned by the emperor, I was determined not to accept. But he, as soon as he saw me, embraced me and said to me that he would not let me go unless I told him that I would accept the post of minister and that, if I refused to do this service, he would summon the Liberals and would have to tell everybody that I was responsible for the consequence, all the while encircling me with his arms. I pointed out to him my circumstances, my age, and my infirmity; but he concurred in nothing. To free myself from him, I should have had to shove him off, and this I could not do. I bowed my head and said that I would do what he wanted but that I was sure that he would have cause for regret, since I would not be minister for long, because I would die from work and troubles. However, he listened to nothing and told me that I should only do what I could do but that I must not abandon him, since he would in that case abandon us and go away.[188][189]The elderly Caxias, nearly 72 and widowed since 1874, was in poor health and could only serve as a figurehead president of the government which was created on 25 June 1875.[187] Itaboraí filled the role of de facto president.[190][191] The Caxias-Cotejipe cabinet attempted to placate the discord created by the previous cabinet. Their measures included financial aide to coffee farmers, an amnesty for the convicted bishops, and the selection of new ministers and a call for elections to please the pro-slavery Conservatives.[192] Caxias, who was a Freemason himself but also a staunch Catholic and a deeply religious man,[193] threatened to resign if the emperor did not grant the amnesty, which Pedro II grudgingly issued in September 1875.[194]

Death

At the end of 1877, Pedro II paid a visit to Caxias and ascertained that he could no longer stay in office[195] and the entire cabinet resigned on 1 January 1878.[196] His health problems had become so troubling[197] that he had asked repeatedly to resign since early 1876.[198] Caxias was not only afflicted by concerns over his declining health, but increasingly felt a sense of alienation. The Duke no longer saw himself playing a relevant role in politics.[9] He belonged to an older generation who perceived the Emperor (and consequently, the monarchy) as being an essential factor in holding the nation together.[199]

The new politicians who had begun to dominate the government had little memory of times before Pedro II assumed control in 1840. Unlike their predecessors, had no experience of the Regency and early years of Pedro II's reign, when external and internal dangers threatened the nation's existence. They had only known a stable administration and prosperity.[199] The young politicians saw no reason to uphold and defend the Imperial office as a unifying force beneficial to the nation.[200] Times were changing fast, and Caxias was aware of the situation. He became increasingly nostalgic for the old times he had spent with his now-dead Conservative Party colleagues and held pessimistic views of future political prospects.[115] When Itaboraí—one of the last survivors of those Conservative leaders who had begun their careers during the 1830s—died in 1872, the Duke wrote to a friend: "Who will replace him? I dont know, I cannot see... The vacuum he left will not be filled, as it was not with Eusébio, Paraná, Uruguai, Manuel Felizardo and many others who helped us sustain this little church [i.e., the monarchy, his "second faith"], which collapsed or almost collapsed on 7 April 1831."[115]

Confined to a wheel chair as his health slowly declined, the Duke of Caxias lived his remaining days at his Santa Mônica farm, located in the countryside of Rio de Janeiro province.[201] On 7 May 1880 at 11 p.m.,[202] he quietly died, attended by members of his family.[203] A saddened Pedro II (who visited Caxias several times during his long illness) remarked about his "friend of almost a half century", that he had "known him, and esteemed him since 1832. He was 76, almost 77-years old. And so we remain in this world."[204]

Caxias asked for a simple funeral, with no pomp, no honors, no invitations and only six soldiers of good conduct to carry his coffin. His last wish was not entirely respected: Pedro II sent a carriage of private use for funerals of members of the imperial family only, to be followed by sixteen servants of the imperial household and one corporal and thirteen, not six, soldiers of good conduct carried his remains.[205] A huge procession was followed by a funeral (attended Pedro II in person[206]) and his body was laid to rest in the São Francisco de Paula cemetery in the city of Rio de Janeiro.[207] On 25 August 1949, his remains, as well as those of his wife, were exhumed and reinterred in Rio de Janeiro's the Duke of Caxias Pantheon.[208]

Legacy

Monument in honor of the Duke of Caxias in the city of São Paulo

At the time of his death in 1880 until the 1920s the Duke of Caxias was not regarded as the most important military historical character in Brazilian history. This place belonged to Manuel Luís Osório, Marquis of Erval.[209][210] Caxias was barely remembered.[211] His memory was slowly recovered and the first attempt happened in 1923 when the ministry of the Army created an annual celebration in honor of Caxias.[212] In 1925 his birthday became officially the "Day of the Soldier", which commemorates the Brazilian Army.[212][213] On 13 March 1962 Caxias became Patrono (literally, "Patron", a kind of "patron saint") of the Brazilian Army, making him the most important figure in the army tradition.[213] According to Adriana Barreto de Souza,[214] Francisco Doratioto[215] and Celso Castro[216] Caxias took the place of Osório because he was seen as a loyal and dutiful officer who could serve as a role model in the Brazilian republic plagued since its birth in 1889 by military insubordination, rebellions and coups d'État.

The historiography is often positive toward Caxias. Since the first well known biography published in 1878 he "has been the subject of several hagiographic biographies", according to historian Roderick J. Barman.[217] Nelson Werneck Sodré said that Caxias, as a historical character, suffers from the same shortcomings as Pedro II. Both have been always presented as irreproachable men. Not that the historian regards them as unworthy, but to him somewhere in the process the human face of each was lost, giving place to "this black and white figure, model of individual virtues".[218]

Nonetheless, to Sodré Caxias was "not only the greatest military commander of his continent [South America], in his time, but [also] a great politician".[219] Moreover, Caxias was "—more than D. Pedro II—the Empire." His respect to the law and his complete obedience to the civilian government were fundamental. "Caxias, who could have been the most powerful caudillo," says Sodré, "exempts the country of caudillism. While, in the Río de la Plata, the Urquizas, the Rosas, the Oribes, caused disaster to their nations and hindered their development, Caxias added to his prestige both his roles in the consolidation of the empire as well in its external victories without ever throwing his sword over the political balance nor taking [by force] political offices for himself."[220]

According to Francisco Doratioto, the Duke "was uncompromising in the defense of the established order, but, once obtained the military vantage over the rebels, he attempted to reach a conciliation, avoiding inhuman treatment toward the prisioners and granting them amnesty". Also, in "his conception the military power was subordinated to the civilian power, and the greatness of the country was associated with to the order and to the established authorities",[221] something quite different from his Hispanic-American counterparts, as well of the Brazilian military of the late Empire and most of the republican era. The historian remarked as well that:

“ The official military historiography avoided making critical references to the command of Caxias in Paraguay,[E] or, yet, in relation to other moments of his career. It tried to build a pure historical icon, without flaws, many times belittling his contemporaries (Mitre and Osório, for example), as it was necessary to diminish other military commanders to greaten the figure of the Duke, until turning him into the Patron of the Army. The artificiality of such creation results in the little empathy from the part of the ordinary citizen for the icon. Caxias in Paraguay had doubts, pride, resentment, and made mistakes; in short, he was a real character, just as the author or reader of this book. Caxias, however, was able to rise above his limitations, imposed on himself great personal sacrifices and incorporated the responsibility of accomplishing the objective... In this context, Caxias was, indeed, a hero; he carried with him, it is true, social and political prejudice of his time, but one can not demand from the past the observance of present-day values. ” Ricardo Salles said that although his character "evidenced a conservative mind, typical of a dominant group of a socially hierarchical society divided by slavery, there is no reason to deduce based on that he conducted the army without regard to reduce to the maximum the human losses, in battle or by diseases". "On the contrary", affirmed the historian, "the military behavior of Caxias, as it was expected from a competent commander, was guided by an adequate preparation of his actions, always carefully planned and executed..." He concluded: "A man of his time, ... Caxias fulfilled his duty."[223]

Roderick J. Barman affirmed that Caxias was not only "extremely powerful in the Conservative party",[224] but also "the country's most distinguished"[145] and "most successful soldier"[225] that "himself had proved his capacity and his loyalty by defeating revolts against the regime"[226] C. H. Haring said that he was "a brilliant army officer", also "Brazil's most famous military figure"[227] and a man "who was genuinely loyal to the throne".[228] Hélio Vianna regarded Caxias as "the greatest soldier of Brazil".[229] To Thomas Whigham, the Duke was "destined to occupy a lofty spot in Brazil's national mythology. He often had to act as a statesman as much as military man" and was "[s]hrewdly competent in both roles".[24]

Titles and honors

Titles of nobility

- Baron (without Greatness) on 18 July 1841.[109]

- Count on 25 March 1845.[230]

- Marquis on 26 June 1852.[231]

- Duke on 23 March 1869.[232][141]

Other titles

- Member of the Brazilian Council of State.[233]

- Member of the Brazilian Historic and Geographic Institute.[234]

- Emperor's war counselor.[233]

- Emperor's aide-de-camp.[144]

- Emperor's veador (gentleman usher).[233]

Honors

- Grand Cross of the Brazilian Order of the Southern Cross.[233]

- Grand Cross of the Brazilian Order of the Rose.[233]

- Grand Cross of the Brazilian Order of Pedro I.[233]

- Grand Cross of the Brazilian Order of Saint Benedict of Aviz.[233]

- Grand Cross of the Portuguese Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa.[233]

Military honors

- Medal (oval) of the Independence War (Bahia).[233]

- Medal of the army in the Oriental State of Uruguay in 1852.[233]

- Commemorative medal of the surrender of the division of the army of Paraguay that occupied the village of Uruguaiana.[233]

- Medal (oval) of bravery "to the bravest ones" (1867).[233]

- Medal awarded to the army, armada and to civil servants in operations in the Paraguayan War (1870).[233]

Notes

- ^ The family name was "Lima da Silva". After the birth of the Duke of Caxias all members changed the name to "Lima e Silva".[4] They were mostly of Portuguese descent,[235][3] but they also had French ancestors.[236]

- ^ All that is known is that Luís Alves signed the minutes of a meeting among officers of the Right and Center Brigades who had decided to send a delegation to their Commander-in-Chief, Pierre Labatut, to petition him to reconcile with officers of the Left Brigade with whom he had become estranged. The meeting had barely ended when two officers of the Left Brigade arrived, bringing news that Labatut had been arrested.[41] The view of historian Affonso de Carvalho is that Luís Alves, whose name appears last in the minutes, signed under protest and felt uncomfortable with the idea of sending a delegation to talk with the commander-in-chief. Taking a part in a plot to remove Labatut from the command and arrest him would have been even more unlikely.[42] Also, unlike his uncle and other relatives in the army, he was not rewarded with any commission by the conspirators.[237]

- ^ Caxias said in the Senate on 19 August 1861: "In my entire life I took as a rule always to obey, without hesitation, all orders from the government. After I entered the parliament, having to manifest a political opinion, I aligned with those [the Conservatives] who, by their ideas and their behavior, seemed to me to offer the greatest guarantees for the order of my country. I have held myself unshakeably faithful to those ideas.[238]

- ^ The previous Allied Commander-in-Chief was the Argentine President Bartolomé Mitre, whom Caxias replaced in two different occasions. The first occurred for a short time, from 9 February 1867[239] until 1 August 1867,[240] when Mitre departed to Argentina. The second and last time happened on 14 January 1868[241] when Mitre was forced to definitely return to his country which was plagued by several rebellions and his Vice-President had died. The position of commander-in-chief was officially extinguished (but not in practice) later on 3 October 1868.[242]

- ^ The Marxist historiography constructed in Latin America during the 1960s and 1970s offered a stark contrast to the traditional view. Although largely discredited today, this historical narrative was taken up by many during those decades. Its most well-known Brazilian advocate "portrayed the conflict as a genocide deliberately perpetrated against the Paraguayan people and Brazil's slave and Afro-Brazilian populations."[243] Historians Hendrik Kraay and Thomas Whigham called the claim an "improbable assertion".[243] The most serious novel allegation against Caxias was that, in a letter supposedly written by him, he asserted that he had "deliberately spread cholera in Corrientes and other [Argentine] provinces hostile to the war effort by having infected corpses thrown into the rivers."[243] Historians Hendrik Kraay, Thomas Whigham[243] and Ricardo Salles[223] have dismissed this allegation, as there is no proof that any such letter ever existed. Lastly, "no evidence that Brazilian commanders deliberately used black men as cannon fodder has come to light, and the number of slaves forced into the army and navy was quite small (about seven thousand)".[243]

References

- ^ Bento 2003, p. xi.

- ^ a b c Morais 2003, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d Carvalho 1976, p. 4.

- ^ a b Souza 2008, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Souza 2008, p. 108.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 108, 565.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 85.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 6.

- ^ a b Souza 2008, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d Souza 2008, p. 109.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 90.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 92.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 93.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 93–95.

- ^ Bento 2003, p. 27.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 93, 109.

- ^ Bento 2003, pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b c d e Bento 2003, p. 28.

- ^ a b Pinto de Campos 1878, p. 27.

- ^ Siber 1916, p. 418.

- ^ Morais 2003, pp. 209–210.

- ^ a b Doratioto 2002, p. 545.

- ^ a b Whigham 2002, p. 62.

- ^ a b Souza 2008, p. 113.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 114.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 114, 120–121.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 124.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 11.

- ^ Barman 1988, pp. 74–96.

- ^ Barman 1988, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Barman 1988, pp. 104–106.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 12.

- ^ Pinto de Campos 1878, p. 34.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 13.

- ^ a b Carvalho 1976, p. 17.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 18.

- ^ a b Souza 2008, p. 137.

- ^ Pinto de Campos 1878, p. 35.

- ^ a b Souza 2008, p. 131.

- ^ a b Carvalho 1976, p. 19.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 133.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 20.

- ^ Barman 1988, p. 107.

- ^ Barman 1988, p. 139.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 23.

- ^ a b Pinto de Campos 1878, p. 37.

- ^ Barman 1988, p. 151.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 26.

- ^ Bento 2003, p. 69.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 179.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 45.

- ^ Barman 1988, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 42.

- ^ Doratioto December 2003, p. 62.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 43.

- ^ a b Carvalho 1976, p. 46.

- ^ Bento 2003, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Barman 1988, p. 162.

- ^ Haring 1969, p. 46.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 206–208.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 198.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 223.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 240–244.

- ^ Bento 2003, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, pp. 52–54.

- ^ a b Souza 2008, p. 565.

- ^ Bento 2003, p. 66.

- ^ Barman 1999, p. 170.

- ^ Lyra 1977a, p. 245.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 258–259.

- ^ a b Bento 2003, p. 30.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Vainfas 2002, p. 548.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 284.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 285.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 312–314, 320.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 335.

- ^ Pinto de Campos 1878, p. 63.

- ^ Needell 2006, pp. 103, 329.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 282, 348–350.

- ^ Barman 1988, p. 209.

- ^ Needell 2006, p. 102.

- ^ Barman 1988, p. 214.

- ^ Needell 2006, p. 103.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 568.

- ^ Needell 2006, p. 110.

- ^ Needell 2006, p. 75.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 369, 391–392.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 281.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 500.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 282.

- ^ a b Morais 2003, p. 70.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 284, 413–414.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 260–262.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 317.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 360.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 383.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 412.

- ^ Barman 1988, p. 210.

- ^ Barman 1988, p. 222.

- ^ Calmon 1975, p. 176.

- ^ Needell 2006, p. 107.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 496.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 512.

- ^ Bento 2003, p. 32.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 542.

- ^ a b Souza 2008, p. 569.

- ^ Barman 1999, p. 123.

- ^ Lyra 1977a, p. 157.

- ^ Needell 2006, p. 116.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 554.

- ^ a b Souza 2008, p. 348.

- ^ a b c Souza 2008, p. 556.

- ^ Barman 1988, pp. 167, 213, 218, 235 and 241.

- ^ Needell 2006, pp. 15, 18.

- ^ a b Pinto de Campos 1878, p. 125.

- ^ a b c Morais 2003, p. 84.

- ^ Needell 2006, p. 133.

- ^ Pinto de Campos 1878, p. 115.

- ^ a b Needell 2006, p. 160.

- ^ Lyra 1977a, p. 164.

- ^ Pinto de Campos 1878, pp. 127, 129.

- ^ Pinto de Campos 1878, p. 135.

- ^ Needell 2006, p. 135.

- ^ Morais 2003, p. 201.

- ^ Morais 2003, pp. 212–213.

- ^ a b c d Needell 2006, p. 174.

- ^ Needell 2006, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Needell 2006, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Needell 2006, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Needell 2006, p. 184.

- ^ Needell 2006, p. 197.

- ^ Needell 2006, p. 201.

- ^ Needell 2006, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Calmon 1975, pp. 660=661.

- ^ Needell 2006, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Calmon 1975, pp. 669–670.

- ^ Needell 2006, pp. 215–216.

- ^ a b c Souza 2008, p. 571.

- ^ Lyra 1977a, p. 227.

- ^ Lyra 1977a, p. 228.

- ^ a b Lyra 1977a, p. 242.

- ^ a b Barman 1999, p. 202.

- ^ Pinho 1936, p. 133.

- ^ Lyra 1977a, p. 229-235.

- ^ Barman 1999, pp. 202–205.

- ^ Lyra 1977a, p. 235-238.

- ^ Barman 1999, p. 205.

- ^ Bento 2003, p. 35.

- ^ Vianna 1968, p. 174.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 234.

- ^ Lyra 1977a, p. 244.

- ^ a b Salles 2003, p. 86.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 252.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 235.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 278.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 253.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 284.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, pp. 280–282.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 295.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 299.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, pp. 321–322.

- ^ Lyra 1977a, pp. 247–256.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, pp. 335–336.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, pp. 329–330.

- ^ a b Barman 1999, p. 223.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, pp. 360–374.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 250-266.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 384.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 266.

- ^ Vainfas 2002, p. 493.

- ^ Scheina 2003, p. 329.

- ^ a b c Doratioto 2002, p. 366.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 252.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, pp. 253–254.

- ^ a b Barman 1999, p. 225.

- ^ a b c Lyra 1977a, p. 246.

- ^ Barman 1999, p. 226.

- ^ Calmon 1975, p. 797.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, pp. 390–391.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 391.

- ^ Barman 1999, p. 261.

- ^ Barman 1999, p. 257.

- ^ Barman 1999, p. 254.

- ^ a b Barman 1999, p. 269.

- ^ Barman 1999, pp. 269–270.

- ^ Lyra 1977a, p. 247.

- ^ Barman 1999, p. 270.

- ^ Nabuco 1975, p. 857.

- ^ Nabuco 1975, p. 862.

- ^ Morais 2003, pp. 166–168.

- ^ Lyra 1977b, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Lyra 1977b, p. 266.

- ^ Nabuco 1975, p. 929.

- ^ Barman 1999, pp. 285–286.

- ^ Lyra 1977b, p. 265.

- ^ a b Barman 1999, p. 317.

- ^ Barman 1999, p. 318.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 288-290.

- ^ Calmon 1975, p. 1208.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, pp. 290–292.

- ^ Calmon 1975, p. 1209.

- ^ Bento 2003, pp. 170, 173.

- ^ Azevedo 1881, p. 166.

- ^ Carvalho 1976, p. 293.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Castro 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Doratioto 2008, pp. 15, 21.

- ^ Castro 2002, p. 16.

- ^ a b Castro 2002, p. 17.

- ^ a b Doratioto 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 28.

- ^ Doratioto 2008, p. 22.

- ^ Castro 2002, p. 20.

- ^ Barman 1988, p. 298.

- ^ Sodré 2004, p. 134.

- ^ Sodré 2004, p. 137.

- ^ Sodré 2004, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Doratioto December 2003, p. 63.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, pp. 392–393.

- ^ a b Salles 2003, p. 87.

- ^ Barman 1999, p. 219.

- ^ Barman 1999, p. 211.

- ^ Barman 1999, p. 88.

- ^ Haring 1969, p. 49.

- ^ Haring 1969, p. 131.

- ^ Vianna 1968, p. 177.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 72.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 570.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 570.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Cardoso 1880, p. 33.

- ^ Vianna 1968, p. 223.

- ^ Souza 2008, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Pinto de Campos 1878, p. 31.

- ^ Souza 2008, p. 132.

- ^ Pinho 1936, p. 125.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 280.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 298.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 318.

- ^ Doratioto 2002, p. 355.

- ^ a b c d e Kraay and Whigham 2004, p. 18.

Bibliography

- Azevedo, Moreira (1881). (in Portuguese)Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro (Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional) 44.

- Barman, Roderick J. (1988). Brazil: The Forging of a Nation, 1798–1852. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1437-1.

- Barman, Roderick J. (1999). Citizen Emperor: Pedro II and the Making of Brazil, 1825–1891. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804735107.

- Bento, Cláudio Moreira (203) (in Portuguese). Caxias e a unidade nacional. Porto Alegre: Genesis. ISBN 85-87578-09-X.

- Calmon, Pedro (1975) (in Portuguese). História de D. Pedro II. 1–5. Rio de Janeiro: J. Olympio.

- Cardoso, José Antonio dos Santos (1880) (in Portuguese). Almanak Administrativo, Mercantil e Industrial (Almanaque Laemmert). Rio de Janeiro: Eduardo & Henrique Laemmert.

- Carvalho, Affonso de (1976) (in Portuguese). Caxias. Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca do Exército.

- Castro, Celso (2002) (in Portuguese). A invenção do Exército brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar. ISBN 85-7110-682-7.

- Doratioto, Francisco (2002) (in Portuguese). Maldita Guerra: Nova história da Guerra do Paraguai. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. ISBN 85-359-0224-4.

- Doratioto, Francisco (December 2003). "Lord of the war and peace" (in Portuguese). Nossa História (Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca Nacional). ISSN 1679-7221.

- Doratioto, Francisco (2008) (in Portuguese). General Osorio: a espada liberal do Império. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. ISBN 978-85-359-1200-5.

- Haring, C. H. (1969). Empire in Brazil: a New World Experiment with Monarchy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0803247869.

- Kraay, Hendrik; Whigham, Thomas (2004). I die with my country: perspectives on the Paraguayan War, 1864–1870. Dexter, Michigan: Thomson-Shore. ISBN 0-8032-2762-0.

- Morais, Eugenio Vilhena (2003) (in Portuguese). O Duque de Caxias: novos aspectos da figura de Caxias. Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca do Exército. ISBN 85-7011-329-3.

- Lyra, Heitor (1977a) (in Portuguese). História de Dom Pedro II (1825–1891): Ascenção (1825–1870). 1. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia.

- Lyra, Heitor (1977b) (in Portuguese). História de Dom Pedro II (1825–1891): Fastígio (1870–1880). 2. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia.

- Nabuco, Joaquim (1975) (in Portuguese). Um Estadista do Império (4th ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Nova Aguilar.

- Needell, Jeffrey D. (2006) (in Portuguese). The Party of Order: the Conservatives, the State, and Slavery in the Brazilian Monarchy, 1831–1871. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-5369-5.

- Pinho, Wanderley; Doria, Escragnole; Lyra, A. Tavares (1936). (in Portuguese)Revista Militar Brasileira (Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional) 35.

- Pinto de Campos, Joaquim (1878) (in Portuguese). Vida do grande cidadão brasileiro Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, Barão, Conde, Marquês, Duque de Caxias, desde o seu nascimento em 1803 até 1878. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional.

- Rodrigues, José Wasth; Magalhães, J. B.; Maul, Carlos (1953). (in Portuguese)Revista Militar Brasileira (Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Militar) 59.

- Salles, Ricardo (2003) (in Portuguese). Guerra do Paraguai: memórias & imagens. Rio de Janeiro: Edições Biblioteca Nacional. ISBN 8533302649.

- Scheina, Robert L. (2003). Latin America's Wars: The age of the caudillo, 1791–1899. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books. ISBN 1574884506.

- Siber, Eduard (1916). (in Portuguese)Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro (Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional) 78.

- Sodré, Nelson Werneck (1998) (in Portuguese). Panorama do Segundo Império (2 ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Graphia. ISBN 85-85277-21-1.

- Souza, Adriana Barreto de (2008) (in Portuguese). Duque de Caxias: o homem por trás do monumento. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. ISBN 9788520008645.

- Vainfas, Ronaldo (2002) (in Portuguese). Dicionário do Brasil Imperial. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva. ISBN 85-7302-441-0.

- Vianna, Hélio (1968) (in Portuguese). Vultos do Império. São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional.

- Whigham, Thomas L. (2002). The Paraguayan War: Causes and early conduct. 1. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803247869.

External links

Media related to Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, Duke of Caxias at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, Duke of Caxias at Wikimedia CommonsPreceded by

Marquis of ParanáPresident of the Council of Ministers

1856–1857Succeeded by

Marquis of OlindaPreceded by

Baron of UruguaianaPresident of the Council of Ministers

1861–1862Succeeded by

Zacarias de Góis e VasconcelosPreceded by

Viscount of Rio BrancoPresident of the Council of Ministers

1875–1878Succeeded by

Viscount of Sinimbu Empire of Brazil

Empire of BrazilGeneral topics Wars Brazilian Independence (1822–1824) · Cisplatine War (1825–1828) · Platine War (1851–1852) · Uruguayan War (1864–1865) · Paraguayan War (1864–1870)Emperors Statesmen José Bonifácio de Andrada · Marquis of Paraná · Viscount of Rio BrancoMilitary Abolitionists Categories:- 1803 births

- 1880 deaths

- Marshals of Brazil

- People of the Paraguayan War

- Nobility of the Americas

- 19th-century Brazilian people

- Brazilian nobility

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Pedro I of Brazil

- Conservative Party (Brazil) politicians

- Government ministers of Brazil

- Brazilian monarchists

- Members of the Senate of the Empire of Brazil

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.